Circles of Apollonius... and magnetism!

These two concepts go together in a very natural way. Prepare for a breathtaking real-world application of Euclidean geometry!

Suppose you have two identical long wires side by side, parallel to each other and connected to each other at one end, and a current is flowing through one wire and back through the other in the other direction. As in this video, each wire generates a magnetic field, and the magnetic field forces the two wires towards each other. The question is, just before the wires start to move towards each other, what does the magnetic field look like?

Let’s simplify the problem a bit. Viewing the wires head-on, we can draw them as two points, and envision one current going into the page (red) and another current going out of the page (blue).

Some basic electrodynamics tells us that the magnetic field vectors generated by one of the wires alone are tangent to the circles centered at the wire, in the plane perpendicular to the wire. Furthermore, the magnitude of these vectors at a distance $r$ from the wire is proportional to $1/r$.

So, we can sketch the magnetic field arising from each wire separately, in two different colors, with the thickness and brightness indicating the strength of the field:

We can add these magnetic fields together to get a single magnetic field that looks like this:

The magnetic field lines appear to be circles! What are these circles?

A very similar-looking diagram recently came up in a class I was teaching on Inversive Geometry at the Math Olympiad Summer Program (MOP) this summer. A circle of Apollonius with respect to two given points $A$ and $B$ can be defined as any circle for which $A$ inverts to $B$ about that circle. Alternatively, and perhaps more simply, it is the locus of points $P$ having a given constant value of the ratio $PA/PB$.

One student in the class pointed out that these circles look very much like a magnetic field of some sort. Intrigued, I asked around and did a bit of research. I found that the circles of Apollonius arise as the equipotential lines of two different point charges.

However, this wasn’t a realization of the circles as a magnetic field. Still curious, I brought the question up at the lunch table the next day. One of my co-workers at MOP, Alex Zhai, suggested to try two parallel wires with opposite currents. Perhaps the magnetic field lines were the circles of Apollonius between the two points that correspond to the wires. It certainly looked correct. How could we verify this?

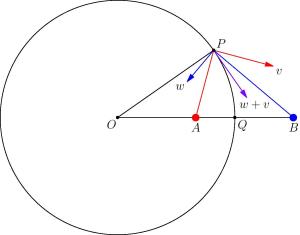

One way to simplify things is to pick one of the circles of Apollonius and make its center be the origin and its radius be $1$. Then, points $A$ and $B$ are on the $x$-axis, at a distance $1/c$ and $c$ from the origin, respectively, for some positive real number $c>1$. Then, pick a point $P=(x,y)$ on the circle, and let $v$ and $w$ be the magnetic field vectors at that point coming from the wires at $A$ and $B$ respectively.

We want to show that the purple vector, $w+v$, is a tangent vector to the circle at point $P$. It’s tangent if it’s perpendicular to $OP$, so in particular, we want to show that the ratio of its $y$-coordinate to its $x$-coordinate is $-x/y$.

But this isn’t hard to show given what we know about $v$ and $w$. These are the magnetic field vectors, so they are perpendicular to $AP$ and $BP$ respectively. This gives us the equations $v\cdot (x-1/c,y)=0$ and $w\cdot (x-c,y)=0$, or equivalently, \[v_1x+v_2y-v_1/c=0\] and \[w_1x+w_2y-w_1c=0.\]

Adding these equations and dividing by $v_1+w_1$, we find \[\frac{v_2+w_2}{v_1+w_1}=\frac{v_1/c+cw_1}{y(v_1+w_1)}-x/y.\]

But we want to show that the right hand side is simply $-x/y$, so it suffices to show that $v_1=-c^2w_1$.

Now, because the strength of the magnetic field is inversely proportional to the distance from the wire, and the circle is the locus of points with a fixed ratio to $A$ and $B$, we also have that \[|v|/|w|=PB/PA=QB/QA=(c-1)/(1-1/c)=c\] where $Q$ is the intersection point of $AB$ with the circle. So, \[v_1^2+v_2^2=c^2(w_1^2+w_2^2).\]

Since we are only interested in the ratio of $v_1$ to $w_1$, let us set $w_1=1$ for simplicity, and try to show that $v_1=-c^2$. If $w_1=1$, then $w_2=(c-x)/y$ from the equation above, and so $w_1^2+w_2^2=(1+c^2-2cx)/y^2$. It follows that \[v_1^2+v_2^2=c^2(1-c^2-2cx)/y^2,\] and we had \[v_1x+v_2y-v_1/c=0\] from before. The values $v_1=-c^2$ and $v_2=(c^2x-c)/y$ satisfy both equations, and so $v_1=-c^2w_1$ as desired.

So there we have it! The circles of Apollonius appear as the magnetic field lines between two parallel, oppositely-oriented, current-carrying wires. Beautiful!